Veronica Nyakoboke laughs as she imagines her “menopause party”—a celebration of what many consider a dreaded transition. “I see it as a powerful new chapter,” she says. But her upbeat attitude wasn’t always there. Like countless Kenyan women, she first faced menopause confused, isolated, and unprepared.

“It was chaos, the mood swings that came out of nowhere, the crushing exhaustion, sleepless nights, and this relentless brain fog,” Veronica recounts, her voice tinged with the memory of frustration. “Nobody warns you about perimenopause, those years of slow transition. Not doctors. Not society. We get endless guidance for puberty, pregnancy, even marriage preparations. But menopause? Silence.”

She pauses, then asks the question that still burns: “Does a woman’s worth disappear when her fertility does? Are we just… discarded after childbearing years?”

That simmering anger became action. She started a simple WhatsApp support group, Ova Circle, and expected a few dozen women to join to share tips and support. But when it hit 2,000 members in just eight weeks, the message was clear: “Thousands of Kenyan women were starving for this conversation, desperate to be seen and heard,” Veronica says. “The silence ends here.”

The Silent Struggle

Her story reflects a broader health and social gap—one marked by misinformation, stigma, and silence.

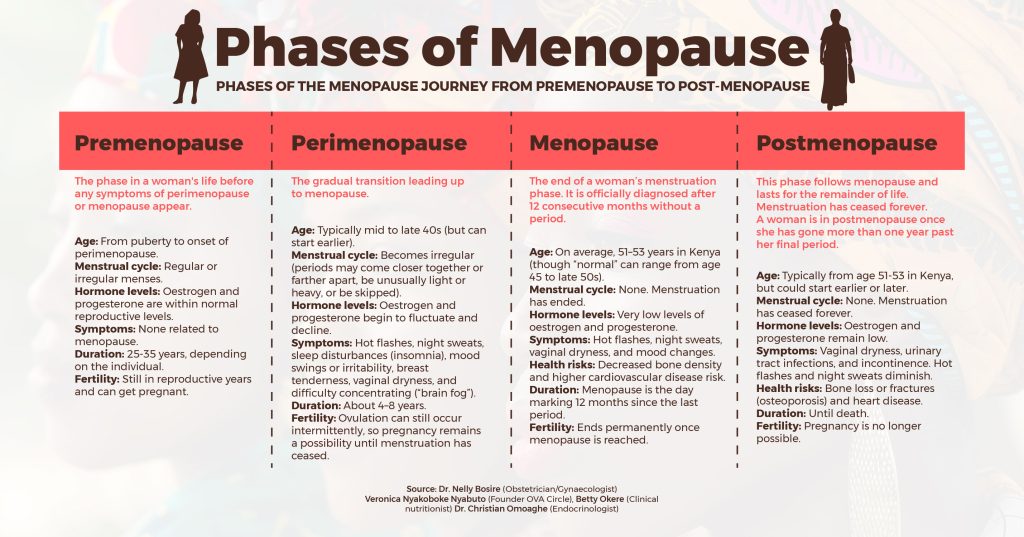

Menopause officially begins after 12 months without a period, but the journey starts much earlier. Dr. Nelly Bosire, a gynecologist, explains that while most women reach menopause between 51 and 53, some experience it as early as 40—or even younger due to surgeries or autoimmune conditions. “Early menopause isn’t just hot flashes. It raises risks for osteoporosis and heart disease,” she says.

Yet, many women don’t realise what’s happening until they’re deep into symptoms. Betty Okere, a dietitian specialising in ageing, says, “They come to me baffled—suddenly gaining weight, aching joints, craving sweets. No one told them these could be menopause signs.”

Over time, the average age of menopause has shifted. While it typically occurred around age 45 in previous decades, it now ranges between 51 and 53, with some women reaching menopause as late as 57. This change is linked to several factors, including better nutrition, improved access to healthcare, declining smoking rates, and advances in managing chronic conditions. Women today also tend to have fewer pregnancies and more access to hormonal contraceptives, which may preserve ovarian function. As life expectancy increases and overall health improves, many women are experiencing a longer reproductive lifespan.

Premature menopause—or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI)—happens before the age of 40 and presents unique challenges. It can be caused by surgical removal of the ovaries due to conditions such as ovarian cancer or torsion, autoimmune diseases like lupus, or unknown factors. POI is linked to increased risks of osteoporosis and cardiovascular complications.

Dr. Bosire explains, “Early menopause between 40 and 45 years is still within normal limits, but menopause below 40 is considered premature and often indicates underlying causes.

Why No One Talks About It

Beyond biology, cultural silence and misinformation make the experience harder.

In Kenya, menopause is shrouded in myths. Some believe it turns women into irritable, irrational versions of themselves. Others assume it starts rigidly at 45. The truth? Every woman’s experience is different.

“Some think menopause means they’re ‘expired,'” Dr. Bosire says. “That’s dangerous. This isn’t the end of vitality—it’s a new phase.”

Dr. Bosire explains the biological process: “Women are born with about two million eggs. By adolescence, only 300,000–400,000 remain. Each menstrual cycle uses 20–30 eggs, and over 40 years of cycles, we run out of eggs, leading to menopause.”

Managing Menopause Through Diet and Lifestyle

Dietitian Betty Okere underscores the importance of preparing for menopause early through nutrition and lifestyle. “Healthy eating should begin early in life,” she says, recommending calcium-rich foods like nuts, seeds, and fermented milk, alongside vitamin D sources such as eggs and lean meat. Despite Kenya’s abundant sunshine, vitamin D deficiency is common, especially among women with early morning commutes and full-body coverings. “Many leave home early and return after sunset. This affects vitamin D levels, contributing to fatigue and grogginess,” Okere explains.

To manage common symptoms like weight gain and blood sugar spikes, she advises eating low-glycaemic carbohydrates such as whole grains, yams, and arrowroots. “These foods regulate blood glucose, improve gut health, and reduce inflammation,” she adds. While supplements can help, Okere cautions against self-prescription. “Supplements should be used to solve known deficiencies, not create excesses,” she warns, urging women to consult professionals. Framing menopause as a natural life transition, not a crisis, Okere calls for open conversations, cultural sensitivity, and supportive environments that help women move through this phase with dignity and confidence.

A Movement for Change

Grassroots efforts are challenging the silence. Podcasts like Pause for Menopause share real stories, while apps like Balance offer science-backed coping tools. Organizations like Marie Stopes and Menopause Solutions Africa host forums where women swap advice and vent frustrations.

But menopause is more than a personal health issue—it has economic consequences. Globally, menopause-related absenteeism and productivity losses cost over $150 billion annually. In Kenya, data is still emerging, but a study among public hospital health workers in Kiambu County found that menopausal women experienced a 38% decline in productivity—twice the rate of their non-menopausal peers.

This issue will only grow. A recent report projects that by the late 2020s, 76% of postmenopausal women globally will live in developing countries, many of them in Africa. With nearly 1 billion women expected to be menopausal by 2025—many at the peak of their careers—there is an urgent need for supportive workplace policies and stronger health systems. In the UK, companies with over 250 employees may soon be required to publish menopause action plans, including paid leave, uniform adjustments, and temperature-controlled workspaces.

“Employers are often completely unaware,” says Ms. Nyakoboke of Ova Circle. “Women suffer in silence because they fear being judged or overlooked for promotions. They’ll lie about what they’re going through because there’s so much stigma.”

Through Ova Circle, she is working with Kenyan companies to develop menopause-inclusive policies modeled on existing frameworks for breastfeeding mothers—offering empathy, flexibility, and dignity in the workplace.

Making Menopause a Public Health Priority

The cost of care remains a major barrier. Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) costs between Sh. 5,000 and 20,000 per month, out of reach for many. HRT also isn’t suitable for all; it carries risks for women with hormone-sensitive cancers and requires thorough medical screening.

To address this, the Ministry of Health should integrate menopause care into national health insurance schemes to make support both accessible and affordable. It must also be prioritised in national health policies, not just because of the rising numbers, but due to its ripple effects on mental health, workforce retention, and long-term wellbeing.

That means investing in local research to better understand symptom patterns, social stigma and real needs. Reliable data will drive responsive, equitable policies that reflect the lived experiences of Kenyan women.

By making menopause care a public health priority, Kenya can support millions of women navigating this life stage—and reshape how we address women’s health across the life course.

Veronika Nyakoboke’s journey from confusion to advocacy highlights the urgent need for Kenya to move beyond silence—by embedding menopause into national health policy, investing in research, and building systems that ensure no woman faces this life stage without care, dignity, and support.

This article was produced as part of the Aftershocks Data Fellowship (22-23) with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).